Open Stores: The Things We Keep

Welcome to our learning resource accompanying the exhibition Open Stores: The Things We Keep. This guide explores twelve selected artworks and archival objects held in the University’s stores, revealing what we choose to keep and why.

Objects range from 19th-century earrings made from Thomas Holloway’s hair to modern self-portraits by contemporary artists. Each object tells part of the University’s evolving story. The twelve featured works are grouped into four thematic sections:

· University History

· Travel

· Societal Change

· Contemporary Acquisitions

Each section includes:

· Descriptions of key objects

· Artist and historical context

· Prompts and questions for reflection

University History

Many of them items in the University’s collection relate to its history. Sometimes the link is obvious, particularly when depicting something with a tangible link to the college today. For instance, when looking at John Piper’s painting of Royal Holloway (also in this exhibition), we see the same familiar Founder’s Building that stands today looking back at us. The works selected here for further exploration have a less immediately visual link to the University but are no less embedded its history

Item One: Charles Packer (c.1826–1932) Earrings Made from Thomas Holloway’s Hair (1855–1875), jewellery (2024.2)

These earrings were made using the hair of Thomas Holloway and gifted to his wife, Jane. In the Victorian period, jewellery incorporating human hair was both a fashion and an art form. When created from the hair of the living, it was considered sentimental or decorative. When made from the hair of the deceased, it became known as mourning jewellery.

This finely crafted pair was made by Charles Packer, whose firm held a royal warrant. The attribution caused some friction with the original business owner, Antoni Forrer, who claimed Packer was unfairly profiting from his name.

This object offers a deeply personal connection to the Holloways and reflects changing ideas about art, love, memory, and fashion.

Item Two: John Brett (1832–1901) Carthillon Cliffs (1878), oil on canvas (THC002)

At first glance, this may seem like a typical Victorian landscape. But John Brett’s Carthillon Cliffs is full of subtle detail and meaning. The view near Penzance (close to Thomas Holloway’s home) is one of several Cornish landscapes in the collection.

Look closely and you’ll see sheep grazing among the rocks and lichen. These were once common in the area but had disappeared. When contemporary artist Kurt Jackson selected this painting for his exhibition Flora: 150 Years of Environmental Change in Cornwall at Penlee House, he shared it with local landscape conservationists. This led directly to the reintroduction of sheep grazing along this stretch of Cornish coastline.

This painting captures a moment in time but also reminds us how art can influence real-world change and help us reconnect with our environment.

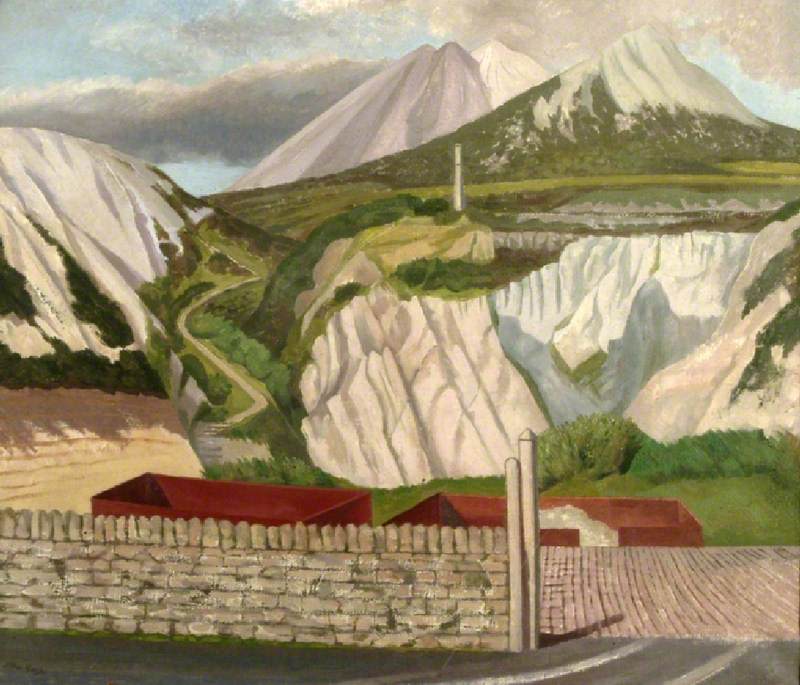

Item Three: John Northcote Nash (1893–1977) Mountain Landscape with Distant Lake (1939), oil on canvas (P1029)

John Nash, one of Britain’s most significant war artists, was also a prolific painter of landscapes. This painting shows a view of Tregonning Hill, near Germoe in Cornwall – less than 10 miles from where Royal Holloway’s founder, Thomas Holloway, once lived.

The scene shows a white, snow-like hill, not from snow, but from the mining of kaolin (a type of clay used to make porcelain). In the late 18th century, apothecary William Cookworthy discovered that the Cornish landscape held a rare form of decomposed granite similar to the kaolin traditionally sourced from China. This discovery led to decades of clay mining, which left visible scars on the land that are captured in Nash’s painting.

This painting tells a story about how people have shaped the land over time. It connects nature, industry, and local history and reminds us that landscapes carry the marks of both beauty and human impact.

Reflective Questions

Why do you think these works are part of the college collection?

How do these works relate to student experience at Royal Holloway today, if at all?

Imagine each artwork as depicting the main scene in a short play — what is the story?

What are the key themes that a landscape painter might seek to depict today? How do these relate to the paintings on show?

How would you describe this item to someone who can’t see it?

What title or caption would you give this object to spark curiosity?

Travel

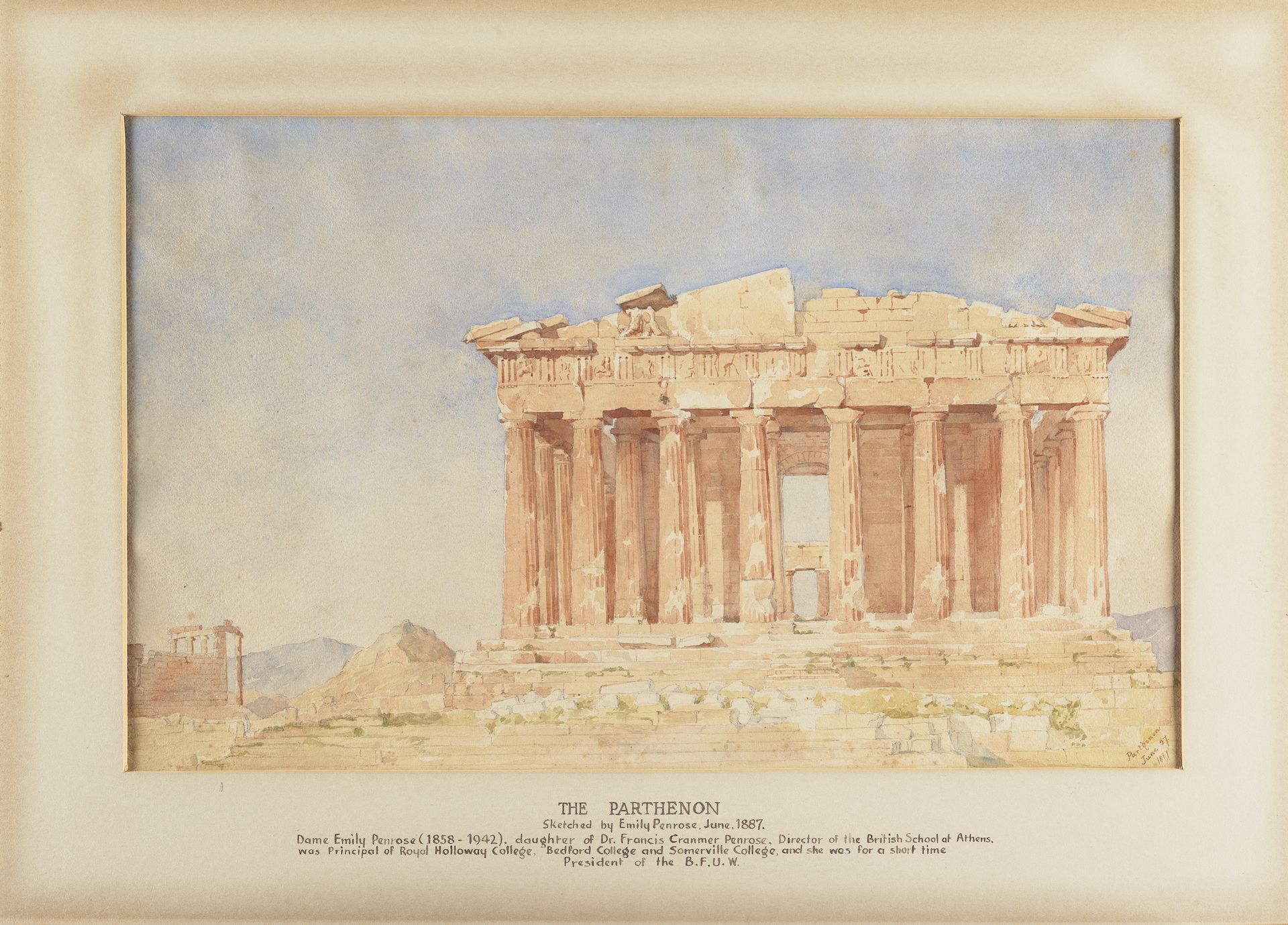

A recurring theme in the University collection is the theme of travel, particularly in the late Victorian era and early 20th-century. This was a time when international travel was rare and a privileged activity. The artists in the Royal Holloway collection who were fortunate to have spent time abroad documented their experiences in various ways. We see this is in Christiana Herringham’s copy of a fragment from the Haṃsa Jātaka, Emily Penrose’s study of the Parthenon and Amy Drucker’s portrait of a girl wearing a headscarf. Whether historic sights of the people, each work seeks to capture something of the places and people they encountered on their travels.

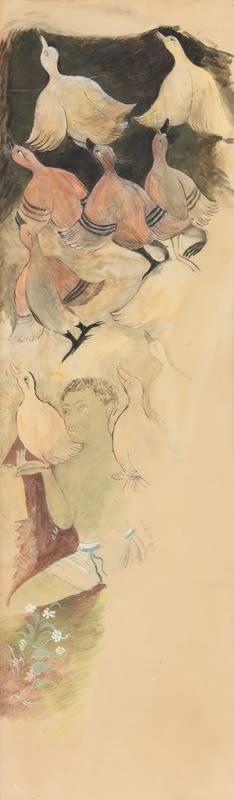

Item Four: Christiana Herringham (1852–1929) Fragment from the Haṃsa Jātaka (c.1909–1911), pencil, gouache, watercolour, tempera on paper (P0913)

Christiana Herringham was an artist, traveller, and active suffragist. She helped found the Women’s Guild of Arts and collected works by other women artists, many of whom are now part of our collection. Her own paintings came to Royal Holloway through the merger with Bedford College in 1985. This piece is based on frescoes from the Ajanta Caves in India, which tell stories from the Buddha’s past lives. The Haṃsa Jātaka shows the Buddha as a goose king. Herringham’s version captures both the geese and the quiet space around them – inviting us to imagine what else the story might hold.

This painting reflects Herringham’s wider mission: to explore, preserve, and champion artistic traditions beyond the Western canon. Her legacy lives on in the diversity of our collection and in the ongoing recognition of her role in shaping a more equal future for women in art.

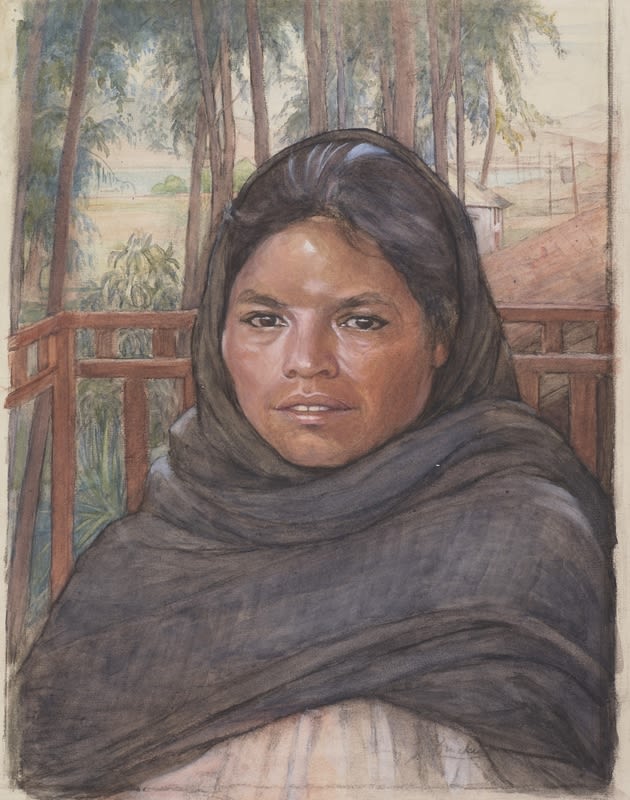

Item Five: Amy Drucker (1873–1951) A Girl Wearing a Black Headscarf (1938), watercolour and chalk on paper (P1677A)

Amy Drucker was a British artist and educator known for her sensitive portraits and scenes drawn from her extensive travels across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Her work focused on capturing everyday life and the dignity of her sitters. During one journey, she was commissioned to paint a portrait of Emperor Haile Selassie – an exceptional recognition for a woman artist of her time.

This portrait of a young girl is part of a group of Drucker works held in the University collection. Its quiet detail and expressive softness highlight Drucker’s skill in using watercolour and chalk to convey mood and character.

This drawing reflects a broad view of portraiture in the University’s collection, one that values lived experience and global perspectives alongside more formal academic traditions.

Item Six: Emily Penrose (1858–1942) The Parthenon (1887), watercolour (2020.3)

Emily Penrose was a pioneering ancient historian and served as Principal of Bedford College, Royal Holloway, and Somerville College, Oxford. This watercolour was made during her youth while living in Athens and it captures one of Europe’s most iconic classical sites through her own eyes.

Penrose is a key figure in the University’s history, and this painting offers a more personal insight into her early experiences.

This work reflects Penrose’s deep connection to the classical world and to the college. It also reminds us that art often sits alongside other pursuits – something many of us can relate to in our own busy lives.

Reflective Questions

What emotions does each artwork evoke in you? Why?

What question would you ask visitors to get them to think more deeply about each artwork?

How do these artworks relate to themes of travel?

What draws you to each artwork?

How might the experience of travel abroad differ in the period when these works were made opposed to the present day?

How might the way we view these artworks have changed since the day they were made?

Societal Change

Many of the works in the University’s collection reflect the way in which society has shifted, changed and been transformed in the years since Thomas Holloway started the collection. In the works below, we explore how Sarah Bernhardt forged a path for other female artists, working across both visual and performing arts. In Laura Knight’s etching, she depicts leisure time in the form of a trip to the circus. Yet, it is also an image of labour and of working life, with the circus performers the main subject of the image. It is a reminder of the often-low paid workers who maintain the entertainment industry. A third image shows another etching, this time by Christopher Nevinson. In common with Knight, it depicts someone at work. Yet, Nevinson’s emphasis feels different. His etching shows a rooftop bar in New York; full of energy and life, the image provides a contrast from the austerity of post-war Britain. Each work embodies transformative societal change, a recurring theme in this exhibition.

Item Seven : Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) Le retour de l’église (1879), oil on board (P0492)

Best known as a celebrated actor of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Sarah Bernhardt was also an accomplished artist. She moved in the creative circles of her time, building friendships with many famous figures, from writers like Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and Émile Zola to painters such as Georges Clairin and Louise Abbéma.

Her place in the Royal Holloway collection reflects both her cultural status and the desire to collect outstanding works by women artists.

This painting is important to us because it reveals a side of Bernhardt that many people don’t know. She wasn’t just a star of the s

also helps us celebrate the work of women artists in our collection, many of whom were overlooked or forgotten in their own time.

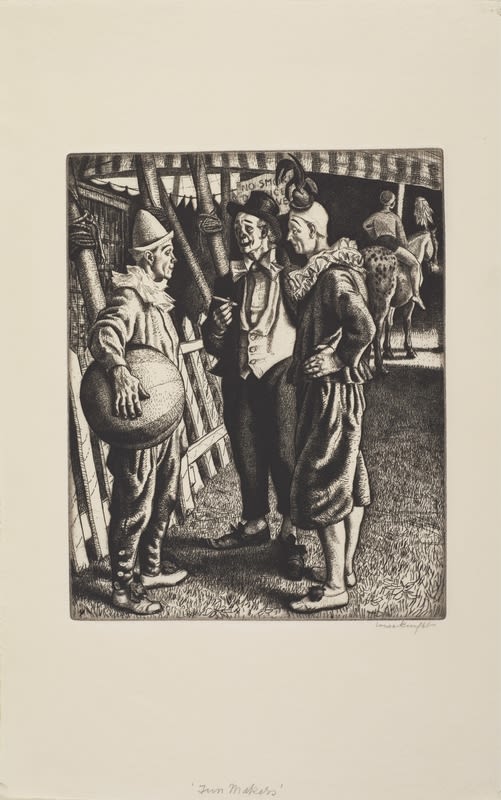

Item Eight: Laura Knight (1877–1970) Fun Makers (1932), etching on paper (P00767A)

Laura Knight was the first woman to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy in 1936, a milestone she credited to the groundwork laid by Annie Swynnerton, another artist represented in the University’s collection. Swynnerton became the first female RA member, but was only eligible as a 'Retired Associate' due to the institution’s age limits at the time.

Knight’s success came in a male-dominated art world, and she used it to open doors for other women. Her work often celebrated performers, everyday life, and working women with energy and empathy.

This etching marks a breakthrough moment for women in art and represents Knight’s vital role in changing the landscape for future generations.

Item Nine: Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889–1946) The Roof Gardens (1919), mezzotint etching (P1518)

This print was inspired by a rooftop club Nevinson visited in New York, after being told by a salesman that such places didn’t exist. Later that night, he saw the same man dancing among friends, highlighting the city's performative charm and contradictions.

Nevinson used the mezzotint technique for this work, a method known for its ability to produce deep shadows and soft tonal transitions. By roughening the surface of the plate and then smoothing areas to create lighter tones, mezzotint allows for dramatic contrasts of light and dark. In The Roof Gardens, the sweeping spotlights cut through the darkness like searchlights, echoing of Nevinson’s wartime imagery.

This work shows us how glamour and grief coexisted in the early 20th century. Through the rich tonal range of mezzotint, Nevinson evokes both theatrical spectacle and lingering trauma.

Reflective Questions

What might these works say about what we value — or used to value — as a society?

What time period or cultural moment do these artworks seem to belong to?

How would a child or elder view these artworks differently?

What moment would you pick to depict the way society has changed in your lifetime?

What is the role of art in reflecting changes in culture and society?

What other work(s) in the exhibition do you feel embody some kind of societal change?

Contemporary Acquisitions

The Royal Holloway collection was started by Thomas Holloway in the second half on the 19th-century. Since its early days, contemporary collecting was at the heart of the University collection. Accordingly, across the collection, we see works from the Victorian era to the present day. We have selected three works, all portraits made by contemporary artists. Each is very different but asks what it means to make art today. How has the art world changed from Thomas Holloway’s lifetime to the present day? How might the type of artwork that a University or institution seeks to collect have changed over the past century?

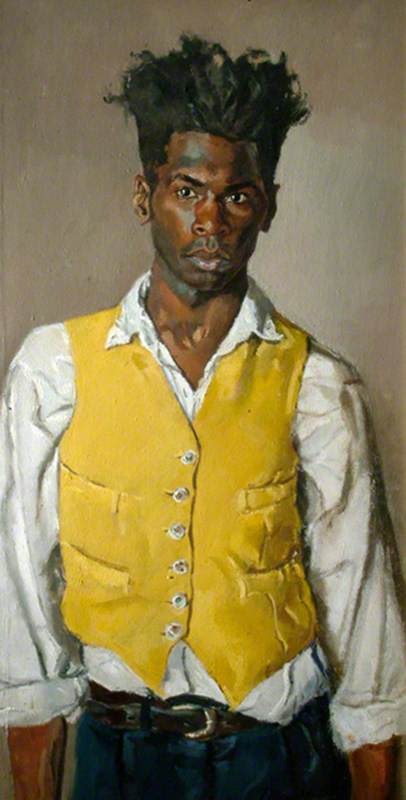

Item Ten: Desmond Haughton (b. 1968) Self Portrait in a Yellow Waistcoat (1993), oil on canvas (P1620)

The Royal Holloway stores contain many portraits. The oldest ones usually show former University Principals. More recent works, like this self-portrait by Desmond Haughton, look beyond the University itself. They continue the tradition of portraiture while asking what it means today.

Haughton, a Black artist, remembers visiting the V&A and National Gallery as a teenager. He noticed that Black people were rarely shown as individuals in the artworks. His portrait work responds to that absence and aims to reflect his own identity and community. This painting was recently shown in an exhibition at Ferens Gallery in Hull, curated by artist Nahem Shoa. Shoa is also the subject of a portrait by Louise Courtnell, held in the University's collection.

We keep this painting because it helps us tell a fuller story of who is represented in art. It reminds us that portraits aren’t only about famous people – they’re also about identity, inclusion, and seeing ourselves.

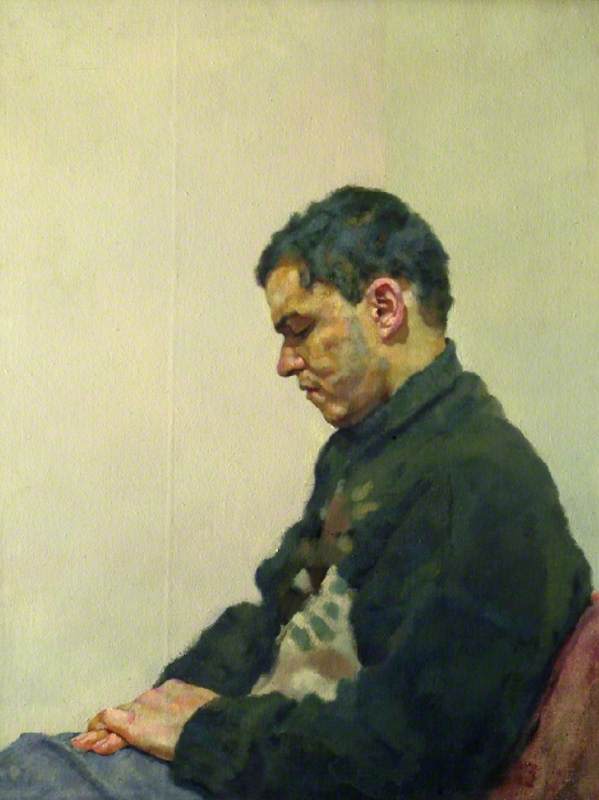

Item Eleven: Louise Courtnell (b. 1963) Mr Shoa the Younger (1992), oil on canvas (P1622)

This portrait shows artist Nahem Shoa, painted by his close friend Louise Courtnell. The two trained together as apprentices under Robert Lenkiewicz. Like Desmond Haughton’s self-portrait (painted just a year later) this work highlights an important gap in the University’s collection.

Because Royal Holloway began as a women’s college, the collection includes many portraits by and of women. But portraits by and of artists of colour are far less common. This work helps address that imbalance.

This painting shows us how the collection has changed over time. Today, we continue to build a collection that reflects both the University’s diverse community and wider society.

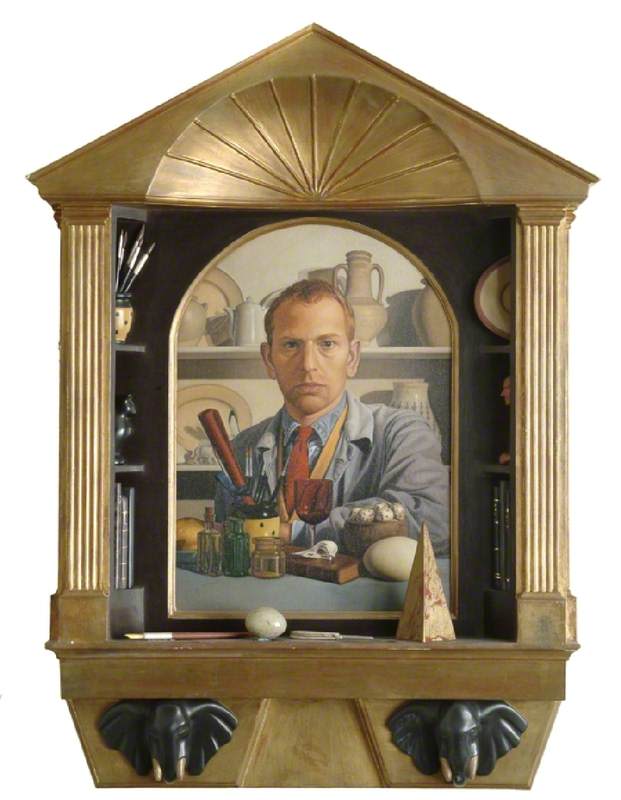

Item Twelve: Steven Hubbard (b. 1956) Self Portrait with Objects (1993), mixed media on board (P1623)

Steven Hubbard’s striking self-portrait was one of six contemporary works acquired by the University in the 1990s to expand and modernise the collection. Blending painting with sculptural elements, the piece challenges traditional portraiture by bringing personal objects into the frame – books, a quail egg, an Egyptian cat, and paintbrushes.

Hubbard invites us to think about how we construct identity. His use of mixed media offers a playful but considered take on self-representation.

This painting pushes the boundaries of what a portrait can be. It invites curiosity and encourages us to consider how we might represent ourselves.

Reflective Questions

If you were to paint a portrait today, what do you think your image would try to capture?

If you were to commission a portrait for the University collection, who would the subject be and why?

If the paintings above represented human traits (hope, fear, ambition, etc.), what would they be?

What differences can you see between the contemporary works in the University collection and the historic ones? This could refer to the way they are painted or the subject matter.

When you see portraiture in art galleries today, what does it make you think of and why?

In Steven Hubbard’s self-portrait, we see a selection of sculptural objects used to complement the painted portrait. What do these objects tell us about the sitter than a more conventional portrait might not?

Explore. Reflect. Question. These are the things we keep.