Painting and Copyright in the Nineteenth Century

The golden age of the living painter and the emergence of modern copyright

In this online exhibition, Dr Elena Cooper, the author of Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (CUP 2018), goes back in time to the nineteenth century. The nineteenth century is significant both to art history – as the ‘golden age’ of the living painter – and to copyright history – as the time of the emergence of modern copyright. In bringing these two scholarly perspectives into conversation, this exhibition explores the connections between Victorian painting and copyright history.

How does closely engaging with painting help us better to understand copyright history? And how does copyright history help us better to understand painting?

There is no better place to explore these questions as regards the nineteenth century, than the Picture Gallery at Royal Holloway, University of London, a gallery that holds what, in the nineteenth century, was seen as one of the very best collections of modern art.

Introductory room

The Collection was acquired by the College’s founder, Thomas Holloway (1800-1883) in a three-year spending spree between 1881 and 1883. Thomas Holloway was a Victorian entrepreneur who made his money through the sale of patented pills and ointments, and he founded Holloway College – a women’s education college – in memory of his wife Jane (née Driver, 1814-1875) who had also been a partner in the medicine business.

The Royal Holloway Collection remains today almost entirely Victorian; it is a time-capsule for the cutting-edge modern art of the past. And, as we will see in this exhibition, in transporting us to that past time, the Gallery can bring a crucial period in copyright history to life.

William Scott (active 1840s), Thomas Holloway, 1845, oil on canvas, 115.6 x 83.7 cm.

William Scott (active 1840s), Thomas Holloway, 1845, oil on canvas, 115.6 x 83.7 cm.

William Scott (active 1840s), Portrait of Jane Holloway, 1845, oil on canvas, 112.9 x 86.3 cm.

William Scott (active 1840s), Portrait of Jane Holloway, 1845, oil on canvas, 112.9 x 86.3 cm.

Room 1

In Spring 1862, this painting – The Railway Station by William Powell Frith – was first unveiled to the public. People came in droves – over 21,000 spectators in just 7 weeks - to the Gallery at no 7 Haymarket in London’s West End. Held back by railings, the crowds were urged to shuffle along and not to stop, so all could catch a glimpse of what was seen as a ground-breaking work of modern art.

Frith had already excited the public with his panoramic paintings of crowds at the seaside - Ramsgate Sands - and at the races - Derby Day - pictures that were said to capture the ‘sparkle of modern life’. But the busy crowd at Paddington railway station was Frith’s most ambitious subject yet. The railway was a symbol of Victorian modernity, and press reviews of the picture reflected that: the steam engine, exclaimed the Illustrated London News ‘is the incarnate spirit of the age’; the railway had ‘infinitely varied relations’ in ‘English life’, and Frith had captured every class, every character and every expression.

As the crowds stood in wonder, absorbing every detail of what was seen as Frith’s masterpiece, heated parliamentary debates were taking place in Westminster about a new copyright law: the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862. The 1862 Act is significant as the very first UK copyright Act to protect painting. Further, the 1862 Act introduced statutory regulation of certain types of ‘art fraud’, for which penalties could be recovered by any ‘aggrieved’ person. Through close engagement with works in the Royal Holloway Collection, this exhibition brings to life the complex interests that shaped the debates surrounding these legal provisions, including those of artists, collectors, printsellers and the public.

Room 2

The second half of the nineteenth century was a time of intense debate about art and copyright. Paintings by living artists were being sold for record high prices, and there was a lucrative market for reproductions of paintings through engraving. Yet, while prints were protected by copyright Acts passed in the eighteenth century, painting was unprotected by statute until 1862.

Copyright was a question that painters really cared about and many of the painters whose work is on show in the Gallery were vocal in the nineteenth century copyright debates. William Powell Frith and John Everett Millais, for instance, both supported the campaign that culminated in the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862. Millais and Firth both signed a petition to the House of Lords in 1858 and Frith was one of a group of artists who met the Prime Minister Lord Palmerston to discuss copyright reform in 1860. Painters had both financial and reputational concerns about the widespread circulation of unauthorised copies of their paintings, both copies in the same medium as the original (oils or watercolour) that were passed off as original works, as well as unauthorised photographic copies of engravings they had authorised.

In this room, we can see the two paintings by Millais in the Royal Holloway collection: historical works that tell stories about royal children who died in captivity. In the Princes in the Tower, Millais portrays the fear of the two sons of King Edward IV, in the Tower of London, the shadow on the wall indicating that their assassins may be approaching. In Princess Elizabeth in Prison at St James’s, Millais depicts a daughter of King Charles I, imprisoned at St James’s Palace and writing a letter to the Parliamentary Commissioners, requesting the return of her servants.

The nature of art at this time – the importance of storytelling through painting – is a key to understanding nineteenth century copyright debates; painters sought the freedom to tell and re-tell stories through multiple versions of their works, without the interference of collectors. How copyright could accommodate that freedom, while also protecting painting as a unique object, was a deeply divisive issue. We will explore those debates later in this exhibition (in Room 5). Now we turn to landscape painting – the work of John Linnell and Benjamin Leader – as a way into uncovering the relevance of the criminal law (and its absence) to nineteenth century copyright history.

John Everett Millais (1829-1896), The Princes in the Tower, 1878, oil on canvas 147.2 x 91.4 cm.

John Everett Millais (1829-1896), The Princes in the Tower, 1878, oil on canvas 147.2 x 91.4 cm.

John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Princess Elizabeth in Prison at St James’s, 1879, oil on canvas, 144.7 x 101.5 cm.

John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Princess Elizabeth in Prison at St James’s, 1879, oil on canvas, 144.7 x 101.5 cm.

Room 3

When painters petitioned Parliament in the early 1860s, complaining of an absence of legal protection for painting, they also referred to gaps in the criminal law. In 1857, the Victorian art-world was shaken by a high-profile criminal law ruling: an art dealer – Thomas Closs – who had been found guilty of forgery at common law by a jury at the Old Bailey, had his conviction overturned by an appeal court – the Court of Crown Cases Reserved – and was allowed to walk free from Newgate prison. (We will later see Frank Holl’s depiction of Newgate painted in the 1870s, in Room 7.)

The painting at issue in R v. Closs was a landscape in oils bearing the false signature of the painter John Linnell. On display in this Room, is the example of one of Linnell’s own landscape paintings in the Royal Holloway Collection: Wayfarers.

The prosecution against Closs failed on the counts of obtaining property by false pretences and cheat at common law; there was insufficient contextual evidence relating to the sale. Further, the appeal court held that there could be no forgery. Forgery, held Chief Justice Cockburn, ‘must be of some document or writing’ and the signature ‘Linnell’, applied to a painting, was ‘merely a mark, like any other arbitrary mark on a painting, put on a painting for purpose of identifying it’.

Interestingly, while the property that the criminal law was being asked to protect, was the purchase price paid by the purchaser – the economic investment in the false painting as physical object – John Linnell, who gave evidence in the Old Bailey trial, saw the case as also about safeguarding the integrity of his creative work; he objected deeply to the existence of what he termed a ‘vile copy’. Accordingly, the ‘failure’ of the criminal law implicitly to protect artists, became part of the artists’ case for statutory copyright protection in 1862. Not only that, the perceived gaps in the criminal law, illustrated by R v. Closs, were part of background for the 1862 Act’s regulation of certain acts of ‘art fraud’, which included the fraudulent application of signatures to paintings, actionable by ‘any person aggrieved’ (and therefore protected both collectors and artists.)

Also on display in this room is The Rocky Bed of a Welsh River, an original painting by another well-known nineteenth century landscape artist: Benjamin Leader. Leader also took the stand as a witness in a criminal law prosecution, brought against another art dealer – a Mr Salmon – later in the nineteenth century, in 1885. Salmon had advertised a painting (in fact by an artist called Gallon) as ‘a fine landscape by Leader’, having erased Gallon’s signature and replaced it with the false signature ‘BW Leader’. Leader’s evidence was that the false signature was a ‘deliberate imitation’ of his own: like his own signature, the false signature was in capitals, with the ‘8’ in the date ‘square topped’ as was his usual practice. The jury found Salmon guilty and he was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment.

Benjamin Williams Leader (1841-1923), The Rocky Bed of a Welsh River, 1974, oil on canvas, 121.8 x 91.4 cm.

Benjamin Williams Leader (1841-1923), The Rocky Bed of a Welsh River, 1974, oil on canvas, 121.8 x 91.4 cm.

Room 4

In this room, we return to copyright law and the story of the Fine Arts Copyright Act 1862. One of the biggest problems with the 1862 Act – from the perspective of painters – was its ownership clause: when a painting was first sold by the artist, copyright would lapse – it would be irretrievably lost – unless it was reserved in writing by either purchaser or painter. As a consequence, evidence put forward in the late 1870s to the Royal Commission – a major public enquiry into copyright that reported in 1878 – was that ‘in ninety nine out of one hundred pictures’, copyright would lapse on first sale, leaving the painting completely unprotected.

Accordingly, painters remained concerned about insufficient legal protection against rife unauthorised copying of their works even after the 1862 Act was passed. One of the painters that gave evidence to this effect to the Royal Commission was the painter Erskine Nicol, whose work is on display in this room: The Missing Boat. This painting, originally entitled A Lee Shore, was retitled with Nicol’s consent at the instigation of its purchaser, as ‘The Missing Boat’ ‘intensified the feeling’ (Letter Nicol to College, 6.5.1889, RHUL Archive). It tells the story of an anxious mother looking out to sea with a fisherman for her husband caught in a storm (and again reminds us of the narrative aspect of much nineteenth century art that we will return to in the next room.)

Why did copyright lapse on first sale under the 1862 Act? Copyright in the painting, the protection for the intangible work of the creator, it was argued in legislative debates in 1862, should not fetter the physical property of the collector. Hence, the 1862 Act preserved the status quo on first sale of a painting – no copyright at all – unless there was a written reservation. A further problem was that the ownership clause was drafted in a highly convoluted way; there was a lot of confusion in practice as to what was needed to secure copyright on the sale of a painting, as well as misunderstandings about the status of commissioned works (which were subject to different ownership rules under the Act). And that confusion about ownership of copyright is well illustrated by some of the paintings in the Royal Holloway Collection.

For instance, as regards Erskine Nicol’s The Missing Boat, correspondence in the Royal Holloway archive suggests that neither Nicol nor the purchaser reserved copyright, on first sale in 1877 (letter T.F. Walker to College, 3.9.1904). Therefore, copyright was irretrievably lost. Yet Nicol perhaps thought that copyright in the picture was his: records at The National Archives, London, show that he registered copyright in his name, after first sale of the picture.

Another example of confusion about copyright ownership is John Horsley’s painting The Banker’s Private Room. The painting tells the story of a well-to-do lady negotiating a loan with a banker, while her chaperone looks on with an amused glance. This picture was commissioned, and under the 1862 Act, the commissioner would automatically be the first owner of copyright. However, in archival correspondence held at Royal Holloway, Horsley, referring to copyright law as a ‘vexed subject’, mistakenly thought that, as there had been no mention of copyright on first sale, it was now owned jointly by himself and the College as owner of the physical painting (Letter Horsley to College, 5.6.1888).

Accordingly, even after the 1862 Act was passed, there was general consensus that the law was far from satisfactory. However, as we will see in the next room, there was a lack of agreement as to what the law should be and that stemmed from wider tensions between art collectors and painters relating to a difficult legal question, heavily debated throughout the late nineteenth century: how copyright should treat painters’ repetitions.

And pervading this debate was a legal conceptual question: how to protect the value of a painting as both a unique physical object – the painting on canvas – as well as a reproducible intangible work – the expression of a creator.

Room 5

Nineteenth century copyright debates were intricately bound up with the tensions between collectors and painters. This is apparent from the terms of the very first parliamentary debate in the discussions culminating in the 1862 Act, which took place in July 1858. Lord Lyndhurst, in his opening address to the House of Lords, while stating that copyright should protect painters against the unauthorised reproduction of their work, also referred to two examples where collectors had been aggrieved by painters. In both instances, having purchased an oil painting from a painter, a collector later discovered that the painter had ‘repeated’ the same work, also in oils, and sold the repetition to another collector.

While the painters were not expressly named by Lord Lyndhurst, they were soon identified in the art press as Abraham Solomon and Thomas Faed (and both these artists also feature in the Royal Holloway Collection). The key question was whether painters should be free to ‘repeat’ works they had sold, in the same medium as the original. Should a painter be entitled to paint a second ‘version’ of an oil painting, also in oils, which reproduced the design – the composition – of the original, and then sell that painting to another collector?

On the one hand, painters – such as Solomon and Faed - wanted the freedom to repeat their work. They argued that painting was like a performance or an oral storytelling: so, to repeat a picture, was a retelling of a story. This argument was, of course, closely bound up with the nature of modern painting at this time. Modern art was often about telling a story, as we have seen in the paintings by Nicol and Horsley (Room 3) and Millais (Room 2), or depicting scenes from modern life – like Frith’s The Railway Station (Room 1) – where the interest derives from what is happening in the painting. On display in this Room are paintings by Solomon and Faed in the Royal Holloway Collection: Solomon’s The Departure of the Diligence depicts a scene from modern life – people preparing for the departure of a ‘diligence’ (a type of horse-drawn stage coach) – and Faed’s Taking Rest presents a scene from Scottish life – a mother and child in a highland setting – a palatable depiction of poverty, which would appeal to a middle-class collector (and in contrast to the more socially critical works of the 1870s to which we turn in Room 7).

On the other hand, collectors wanted to prevent painters repeating original works they owned, as the financial value of a painting – the painting as a physical object – was determined by a picture’s uniqueness. Copyright provides protection against copying and therefore privileges the first in time. Accordingly, in the hands of collectors, copyright could be used against artists, to prevent artists from repeating their work, and guarantee the uniqueness and the financial value of the collector’s property.

Copyright proposals favouring collectors were presented to parliament in 1869, 1878 and 1900. Not surprisingly, these pro-collector proposals caused great alarm amongst painters, and the Royal Academy of Arts, spurred into action, forming its own copyright committee to forward its own proposals, presented to Parliament in the 1880s and late 1890s. Painters proposed a very narrow class of ‘repetition’ over which a collector would have control; they also wanted safeguards for painters who sold their pre-existing studies and sketches, as well as for versions specifically created for the purposes of enabling engraving (and the context for the latter is explained in Room 7).

The nineteenth century idea that copyright might also be used against artists, to protect a collector’s financial investment in a physical art object, is quite different to the exclusively pro-artist way we think about copyright today. Interestingly, and revealing the close intertwinement of the aesthetics of painting and copyright, the claim that copyright was also about regulating and restricting artists, only fell away when the nature of art changed in the early twentieth century: in place of the aesthetic of ‘repetition’, art instead focussed on the textured surface that defied repetition. In this new aesthetic context, the argument that copyright should be a means of protecting collectors against artists repetitions, was no longer relevant. Proposals put forward by painters, protecting their right to sell sketches, were then reconceived as a general defence to protect artists from copyright infringement, an early forerunner to the defence we have in section 64 of the UK Copyright Act of today.

Room 6

The nineteenth century copyright debates spanned a broad range of interests, not just concerns articulated by painters (see Room 2) and collectors (see Room 4), but also, as we will now see, the interests of the public. The copyright debates are brought to life by the Royal Holloway Collection because the public significance of the Collection was expressly discussed. This occurred in 1898, as part of evidence considered by a House of Lords’ Select Committee on Copyright about whether a copyright owner should have the right to control the public exhibition of a painting. That debate came out of evidence given by the painter Briton Rivière, whose works An Anxious Moment and Sympathy are on display here.

Briton Rivière gave evidence in 1898, that public exhibition should not be regulated by copyright; it did not involve reproduction. Lord Thring, one of the members of the Select Committee, who was also a governor of Holloway College, agreed with Rivière by presenting the perspective of galleries, like that at Holloway College, ‘thought so good for the public’. Referring to Rivière’s picture An Anxious Moment Lord Thring explained that Thomas Holloway had bought that painting ‘for the purpose… of exhibiting it and cultivating the taste of the neighbourhood’. The notion that the printseller Agnews – the copyright owner of the painting – might control the picture’s public exhibition was, said Lord Thring, a ‘most monstrous’ idea. While only briefly discussed, this characterisation of the Collection also deepens our understanding of its historic significance, beyond the objective stated in Holloway’s Deed of Gift to the College of 1881: that the picture collection be ‘used for the decoration of said buildings and the benefit of the persons entitled to reside therein’.

The debates on the public interest of art to one side, Briton Rivière’s evidence is also significant for another reason: what it tells us about the aesthetic significance of titles of paintings in the nineteenth century. Titles mattered to artists, said Rivière, so as to ‘lead the spectator to see the particular part of the story which the work itself tells’ and that is well illustrated by the two works displayed in this room. An Anxious Moment was met with acclaim when it was first exhibited in 1878, on account of its humour, and the title is clearly intended to draw attention to the humour of anxious geese alarmed by a black hat blocking their path. Similarly, the title Sympathy indicates the importance of the close relationship between young girl and her dog (and, incidentally, is quite different in meaning to the alternative title Gastralgia, The Terror of Childhood suggested by the contemporary satirical magazine Fun.) A change of title, for instance by a collector or a printseller without an artist’s consent (and therefore unlike the case of Nicol’s The Missing Boat discussed in Room 4), to give ‘a bent to the work… which the artist never intended’, argued Rivière, ‘changes his work’. While legislation expressly regulating titles was not introduced, dealing with a painting that had been altered (without the painter’s consent) as if it were unaltered, was regulated, in certain circumstances, by the 1862 Act’s provision on art fraud (section 7, mentioned in Room 3).

Room 7

In the final two rooms of this exhibition, we explore what the Royal Holloway Collection can teach us about the nineteenth century market for reproductions. As already mentioned (in Room 2), the mid to late nineteenth century was a time of unprecedented interest in modern art, and the result was not just record sales for paintings, but also a highly lucrative market for reproductions: prints of popular paintings. For example, Frith’s The Railway Station was engraved by Francis Holl, and prints were published by the printseller Henry Graves in 1862. One objective of copyright reform, then, was better to protect the printsellers’ investment in engravings, particularly in the face of the widespread distribution of cheap unauthorised photographic copies of the engravings. Accordingly, both before and after the 1862 Act was passed, the printsellers Henry Graves and Ernest Gambart led a legislative campaign seeking greater powers for magistrates in enforcing penalties for copyright infringement, penalties which one Court of Appeal case (In re Prince, 1869) held to be in the nature of criminal offences.

The Collection at Royal Holloway also draws attention to another context in which reproduction rights mattered: illustrated journalism. Two paintings of great significance in the Collection are the ‘social realist’ works by Luke Fildes and Frank Holl (son of Francis Holl). Today, we are used to art depicting socially critical subject-matter about the marginalised in society. However, in the nineteenth century, middle class collectors sought subjects that were pleasing to the eye, as well demonstrated by the palatable depiction of poverty by Faed in Taking Rest (Room 5). Consequently, socially critical art first appeared in the nineteenth century as illustrations to literary works, rather than paintings that were independent art-works; true ‘social realism’ in painting did not develop until the 1870s, after the ground had been prepared by illustrated literary publications (both novels and journalism.)

The Royal Holloway Collection holds two prime examples of Victorian social realist painting from the 1870s and rich original correspondence, in the College archive, shows that these artists sought to portray scenes they had directly witnessed in real life. First, Newgate: Committed for Trial (1878) by Frank Holl, presents part of Newgate prison which was known as the ‘cage’, where prisoners awaiting trial were held during visiting hours: to the left and centre, two poor families are visiting, to the right a gentlewoman has entered the area.

Holl painted the picture, having ‘witnessed this scene’ on a visit to Newgate with the consent of its Governor (Letter from Holl to College, 1.9.1887, RHUL Archive).

Of course, far from objective document, this is also a painting imbued with historic notions of criminality prevalent at the time; the story in this picture is also told through the physiognomy of the prisoners. As the art historian Mary Cowling argues, the face of the prisoner on the left is respectable – he is not inherently criminal in nature; by contrast, the features of the prisoner in the centre, are wild and devilish – suggesting he is an innate criminal.

The second painting in this room is Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward (1874) by Luke Fildes, in the opinion of C.W. Carey (the Gallery’s first curator) ‘one of the most important’ paintings in the Collection (Letter Carey to Fildes, 1.6.1888, RHUL Archive). This painting depicts a scene which Fildes also claimed to have witnessed first-hand: a group of homeless people waiting on a cold wintry night, outside a police station, for a ticket for admission to the ‘casual ward’ of a workhouse (as permitted under the Metropolitan Houseless Poor Act 1864).

In correspondence with the College, Fildes explains that that he encountered this scene as he ‘used to ramble about a great deal on Winter evenings, visiting the Police Stations where the applicants assembled’; as a subject from real life, this was a ‘most painful picture for me to work on’ (Letter Fildes to College, 1.6.1888, RHUL Archive).

Interestingly, when the College asked Fildes for his views about reproduction of the painting as a print, he stated that ‘this is what is called a ‘painful’ subject’ rather than ‘charming and pleasing’; ‘such subjects are not paying to publishers’ and therefore ‘a faithful rendering of the Casuals, I fear, would not meet these conditions’ (Letter Fildes to College, 18.4.1890, RHUL Archive). Indeed, and again illustrating the importance of titles at this time (discussed in Room 6), Fildes noted that painful subjects were appealing to publishers when accompanied by a title such as ‘A Martydom’ or ‘Death of ___’ (ibid), but here he had made no attempt to dramatise tragedy; Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward was a factual title, as a scene from everyday life.

Fildes and Holl, then, did not seek to make money out of reproduction on the market for popular prints; as Fildes explained, the subject of the Casuals ‘would not be popular in the trade sense of the term’ and therefore would be a ‘risky’ investment for a publisher (Letter Fildes to College 3.6.1890, RHUL Archive). Notwithstanding this, copyright was central to their artistic livelihoods in another way. Both Fildes and Holl were also illustrators for the most successful publication to feature socially critical illustrations of the Victorian era: The Graphic, an illustrated weekly news magazine, edited by social reformer William Luson Thomas. Indeed, the head-line illustration of the first issue of The Graphic, published on 4 December 1869, was a wood-cut by Luke Fildes of Houseless and Hungry a precursor to the subject developed further in the later oil painting Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward. Copyright in reproductions, then, not just under the Engraving Acts, but more importantly in this context, under the Literary Copyright Act 1842, which protected artistic works which formed part of a book, was key to the existence of such illustrated publications and therefore, to the careers of socially critical artists such as Fildes and Holl.

Room 8

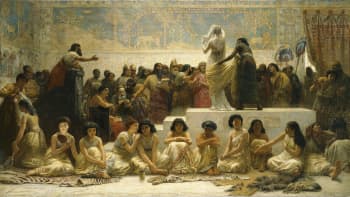

In this final room, we reflect on the impact of technological change in reproduction in the late nineteenth century, by focussing on a single picture in the Royal Holloway Collection: The Babylonian Marriage Market by Edwin Long.

This painting has long attracted attention: met with great critical acclaim when it was first exhibited in 1875, the picture then made a salesroom record when it was sold at Christie’s to Thomas Holloway in 1882 for £6,625 including copyright. Art historians have since studied the subject-matter of the piece – including Long’s intentions in depicting the auctioning of girls without dowries in Babylon – as well as Holloway’s motivation in acquiring it for display in a women’s College. What insights do we gain, if we instead look at the picture from the perspective of copyright history?

Holloway College was opened to the public in June 1886, and two years later, the first secretary to the Governors, J.L. Clifford-Smith, made enquiries about the sale of the copyright to a printseller with a view to the issue of prints after the picture. The printsellers Henry Graves & Co and Thomas Agnew & Sons were both approached but declined the opportunity. Graves & Co considered the subject-matter to be too close to a previous print (probably Long’s An Egyptian Feast reproduced by the Fine Art Society in 1879) such that ‘the copyright… can have little value’ (letter to College from Graves &Co, 8.5.1888, RHUL Archive). Agnews, while willing to make an offer for a ‘picture of such importance’, required a loan of the picture for at least two years to make the reproduction, which was unattractive to the College (letter to College from Agnews, 24.5.1888, RHUL Archive). Consequently, the College pursued negotiations with The Fine Art Society, and a legal agreement was signed on 21 September 1888: the College sold copyright in the picture to the Society for £1,000, and the Society was entitled to possession of the picture for 12 months, so the picture could be reproduced. The print was eventually published on 19 December 1889, signed by both Long and the printmaker Paul Giradet.

Original correspondence in the College archive shows that the path to concluding this arrangement was far from straightforward. As was common at this time, the agreement envisaged that Long would sign the prints, and there were tensions between Long’s interests and those of the College and the Society. In particular, the College wanted to minimise the length of the loan of the picture for reproduction, but Long was concerned about the implications of a short loan for the reproduction technique to be used.

These tensions are clearly articulated in letters written before the copyright agreement was concluded. Long expressed (in a letter to the College’s solicitor Basil Field) that he was ‘really anxious’ that the reproduction ‘if it be done at all, it may be done well’; photogravure, while quicker than line engraving would, in Long’s view, be ‘an injury to the picture and to me’ (Letter Long to Field, 14.5.1888, RHUL Archive). The College’s limit on the time of the loan, however, did not allow time for line engraving, and line engraving would also have been unattractive to the Society on grounds of cost. The Fine Art Society provided Long with examples of successful reproductions of Lord Leighton’s work by photogravure, but Long continued to oppose their plans for his own work. As the Society reported back to the College: ‘Long says Leighton’s pictures photoengrave well, but his don’t’ (Letter from the Society, 13.7.1888 RHUL Archive).

Long was eventually persuaded to agree to photogravure, after the Society provided him with examples of photographs of the picture. However, the story behind the issue of the print offers some insight on the competing interests which required resolution before copyright transactions were concluded at this time. The emergence of cheaper and quicker reproduction techniques like photogravure provided new possibilities for negotiating the interests at stake in art reproduction: reconciling the business of print-making (articulated by printsellers like the Society) with the interests of the owner of the physical canvas (the College’s interests in minimising the time the picture was out of their possession) and the painter’s aesthetic preferences about the nature of the reproduction process.

I hope you have enjoyed this exhibition! For more information, please see the sources listed below or please contact me by email: elena.cooper@glasgow.ac.uk

Dr Elena Cooper is Senior Lecturer at CREATe, the Centre for Regulation of the Creative Economy, University of Glasgow, where she is currently Research Lead for Legal History and Cultural Memory under a £1 million AHRC Infrastructure grant (awarded to CREATe for 2023-2028). She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and the Royal Historical Society, and a member of the British Art Network organised by The Tate to connect experts in British Art. Elena is also Arts Editor for the UK academic journal Law and Humanities.

Elena’s monograph Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (CUP, 2018), the first in-depth and longitudinal history of copyright relating to the visual arts, was shortlisted by the Society of Legal Scholars for the Birks’ Book Prize for Outstanding Legal Scholarship in 2020. It significantly extends Elena’s PhD thesis supervised by Prof. Lionel Bently at the University of Cambridge 2006-2010, which was awarded a Yorke prize, as ‘of exceptional quality’, by the Faculty of Law, Cambridge, in 2011. The research upon which this exhibition is based was funded by The Leverhulme Trust (ECF 1016/016) and a Peter Orton Research Fellowship, Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

Elena would like to thank Bart Meletti (co-Lead for Legal History and Cultural Memory at CREATe) for excellence in design in compiling this online exhibition, as well as Dr Naomi Lebens (curator at Royal Holloway) for her comments on an earlier draft of the exhibition text, and Peggy Ainsworth and Kathryn Saunders (collection managers at Royal Holloway) for their invaluable support and assistance.

Elena’s work with the Royal Holloway Collection began in December 2018, with the book launch of Art and Modern Copyright in the Gallery, made possible by Royal Holloway’s then curator Dr Laura McCulloch. Elena would specifically like to mention Graham Howes (1938-2020), formerly Fellow in Art History, Trinity Hall, Cambridge, for the insights which he shared into the art historical significance of the Royal Holloway Gallery, which shaped her engagement with the Collection.

Sources:

E. Cooper Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (CUP 2018).

M. Cowling Paintings from the Reign of Victoria: The Royal Holloway Collection, London (Frances Lincoln 2008)

J. Chapel and J. Maas Victorian Taste: The Complete Catalogue of Paintings at the Royal Holloway College (Zwemmer 1982)